Dear Sir/Madam,

Suspect: This information is send to the national and international authorities and organisations involved in the Kazakhstan and World Bank Syr Darya and Northern Aral Sea project 2003 - 2006.

We would hereby like to introduce you to the electronic version of the Masterplan for developing the Northern Aral Sea Fishery. The printed plan with figures, pictures and photos and with a complete list of addresses and references to persons and organisations involved, will be ready in the end of May 2003.

- If you need a printed version, please send us a mail llh@levende-hav.dk

The first step of the implementation of the this Masterplan is already started in Aralsk in the frame of NGO Aral Tenizi. The first phase of building up Centre Kambala Balyk, a centre for fish processing and related activities is started in Aralsk. More information about this project will follow in the months to come. If you need this information, please send us a mail.

The Aral Sea from space

The report represents the conclusion of the Danish-Kazakhstani fishery project “From Kattegat to Aral Sea”, which has been working in the Northern Aral Sea (NAS)

region during the past decade to re-establish and sustain a viable fishing trade in the region. By elaborating and distributing this report, the co-coordinators of the fishery project wish to close the project concluding on the history

and experience obtained during the project period, and giving well-founded recommendations for future initiatives in the NAS region.

The report represents the conclusion of the Danish-Kazakhstani fishery project “From Kattegat to Aral Sea”, which has been working in the Northern Aral Sea (NAS)

region during the past decade to re-establish and sustain a viable fishing trade in the region. By elaborating and distributing this report, the co-coordinators of the fishery project wish to close the project concluding on the history

and experience obtained during the project period, and giving well-founded recommendations for future initiatives in the NAS region.

The report contains three chapters, which describe the history of the NAS fishery and the fishery project, the current state of affairs in the NAS fishery, and the recommendations of the fishery project to any parties, which might take an interest in the NAS fishery in the future.

The

NAS fishery is not only a distant dream from the past – it is a real and

valuable trade in contemporary Kazakhstani reality; a trade

which exactly at this point in

time has highly interesting conditions for improvements and expansion. It is

therefore time to shift the focus on the Aral Sea problem from the legend of the

heavy vessels stranded in the desert, to the actual assets available in the sea

and the region, which might come to benefit the inhabitants greatly.

which exactly at this point in

time has highly interesting conditions for improvements and expansion. It is

therefore time to shift the focus on the Aral Sea problem from the legend of the

heavy vessels stranded in the desert, to the actual assets available in the sea

and the region, which might come to benefit the inhabitants greatly.

Centre Kambala-Balyk

On behalf of the NGO Aral Tenizi and Living Sea and the many people who have contributed to the fishery project “From Kattegat to Aral Sea”,

Kurt Bertelsen Christensen

Co-ordinator Kurt B. Christensen, chairman of The Danish Society for a Living Sea.

Juelsgaardvej 27, Ferring Strand

DK-7620 Lemvig

Phone 00 45 97 89 54 55

Fax 0045 97 89 54 55

Mail llh@levende-hav.dk

Masterplan

Setting the Course for the Northern Aral Sea Fishery

INTRODUCTION

The Aral Sea is entering a stage of renewed transformation. Since the 1960s, the changes in the marine and surrounding environment have been almost univocally to the worse; the water level was falling, the salinity rising, the fishery disappearing, villages abandoned. The consequences of the vast irrigation project on the “Virgin Lands” during the USSR of the fifties and sixties, proved to be catastrophic. At present day, the image of Aral as a shrinking and in effect dying sea has been spread and accepted world wide. Who hasn’t seen the stranded ships in the desert, or the sequel of figures or satellite photos, picturing the withdrawing coastline with a prognosis of the total or almost total drying out in the year 2000, 2010, or which ever point in the future that seemed adequately remote at the time?

But the image of Aral is about to change. Since 1996, the inhabitants of the Aral region at the Northern part of the Aral Sea have built a basis for a transformation in the opposite direction. Starting from a grass root level, in cooperation with authorities and scientific expertise, the people of the Aral region have worked industriously to make their voice heard in the national and international community: The Aral Sea is still worth fighting for, it represents a variety of natural assets, which have long been unused, and which can relatively simply be nurtured to become the basis of a new virtuous circle in the development of the region. Beginning with an ambitious and successful trial fishery from the village Tastubek in 1996, thousands of people in the region have taken part in re-establishing a fishery on the sea, and in rising the attention and awareness of the perspectives for the development of the region as a whole. The fishermen are returning to the villages. 90 new brigades and cooperatives have been established, counting over 600 active fishermen. The remaining facilities in fish treatment and transportation have been put into work again, and new added. A number of smaller, private enterprises have been engaged in treating and selling fish from the region centre. And an independent democratic NGO, the Aral Tenizi, has been created to work for the re-establishing of the sea, and for supporting the fishermen and their families in the transformation phase. Today, the aims of this society are shared by local, regional as well as national authorities, and actively supported by a growing amount of volunteering NGOs in the villages and towns around the Northern Aral Sea.

This report aims at describing the background of these changes, and the possibilities they offer for maintaining and improving the positive development in the Northern Aral Sea fishery. Its basic claim is that this development has already started, on the basis of a broad and engaged involvement on a number of levels, including private, public and civil society, and that the urgent task now is to set the course for the future in accordance with the results and experience attained. Managing the portfolio of assets in the Aral region in a sustainable way to the benefit of its inhabitants, depends to a high degree on the direct involvement of the people concerned: the fishermen, their families, the private, civil society and public organisations and institutions. Therefore, the strategy for the future investments in the fishery sector should have as its basic tenet the ambition to support decentralized solutions and independent business structures. The responsibility of the development of the fishery can only be managed in a sustainable way by the fishermen themselves. To optimize the effects of future initiatives therefore, a direct contact with the fishermen and the main engineers of the development in the ecological, economical and organisational awareness in the region is needed.

The report is divided into three main chapters.

In the first chapter, the background of the current situation is described at some length, in order to shape the understanding of what it is, we are dealing with here: Not a random choice of employment for some group of people in the poorest part of Kazakhstan, but a serious and well founded attempt to revive a trade and an economical structure, which have earlier been developed to a high level, with many skills and potentials still available in the region, but which have been sacrificed at the benefit of an intense – and, as it turned out, in itself unsustainable – irrigation scheme. This chapter also tells the story of how the ambitions to revive the Aral Sea fishery appeared and were developed in the Danish-Kazakhstani cooperation, the results and experiences of which are the basis of the entire report.

In the second chapter, a detailed picture of the current situation in the Northern Aral Sea fishery is drawn; this includes separate parts on the resource, the fishermen, the transportation and treatment, the market, the NGO, and the authorities. As it will appear, in each of these fields there are most valuable assets available, which should be managed in an inclusive way, i.e. in a way such as to maintain and further the involvement of as many geographical, economical, and social parties as possible.

In the third chapter, the fishery project From Kattegat to Aral Sea, concludes on its results, and gives recommendations for the strategies to be employed in the future efforts to sustain and further develop the virtuous circle in the Northern Aral Sea fishery. These recommendations should be seen as a concrete attempt at providing the local and national authorities in Kazakhstan with our suggestions, as well as inspiring and encouraging international development agencies to build on the foundation already put down, rather than going through a troublesome quest for the right course in the fishery component of any ambitious development scheme for the Aral Sea basin. The recommendations are based on interviews with fishermen and NGO workers in the Aral Region, and in Denmark.

This report was originally encouraged by the advent of the agreement between the Kazakhstani government and the World Bank, as of February 2002, on the Syr Darya Control and Northern Aral Sea project. Planning for the concluding year of the fishery project, which is financed mainly by the Danida (Danish Development Agency), the Danish co-ordinators had in mind to invite potential donors, together with government and administrative representatives, to a conference in Aralsk on the course for the future development of the fishery in the region. Once it was clear however that the Aral fishermen do in fact have the attention of their own government, as well as of the international community (in as far as this may be represented by the World Bank), it was decided instead to give more direct recommendations for these very welcome initiatives. Being the only practical initiative in the fishery sector of the Aral region since 1994, the fishery project “From Kattegat to Aral Sea” should share its experience, and give its best recommendations for future initiatives.

In the period from the 20th of September to the 19th of October 2002 therefore, a group of four conducted a fact finding mission for this report: From Kazakhstani side Akmaral Utemisova (Aralsk) and Zhannat Makhambetova (Almaty), and from Danish side Jan Hertel-Wulff (fishery consultant) and Henrik Jøker Bjerre (The Danish Society for a Living Sea). During this month, visits were paid to all the significant fishing settlements around the Northern Aral Sea, incl. the four new receiving stations, interviews were made and meetings held in Aralsk, in oblast centre Kzyl-orda, and in Almaty and Astana. The results of this mission will mainly be found in the second and third chapter. The first chapter is based on both written sources (when possible first hand, e.g. from the statistical office in the Aral region, from the archives of the fishery factory Aralrybprom, etc.), and on direct experience from the fishery project.

Author of the report is M.A. Henrik Jøker Bjerre, member of the board of the Danish Society For A Living Sea, and participant in the fishery project since 1994.

Chapter 1: Stranded boats and staying nets

The pictures of the stranded fishing vessels in the desert, which was formerly the bottom of the Aral Sea, have been printed, broadcast and distributed world wide through a couple of decades. These impressive iron bodies of as much as 200 tons invoke the entire story of the once affluent and well structured fishery community, which was quite literally deserted by its political leaders. Such has the image of the Aral Sea and in particular its fishery since been comprehended: A super tanker stranded in the desert with no hope of rescue. And there is some truth in this metaphor, of course. The vast and significant fish treatment sovkhoz, the Aralrybprom, which was the heart of all fishing industry in the region, employing thousands of workers and fishermen at its peak in the early 1960s, is today but an empty ground with one lonely shivering building remaining from the elaborate community of offices, laboratories, workshops, freezing facilities, cold storages, etc. And the vessels themselves have in fact been given up, rusty, fragile and lonely as they lie there in the company of only cattle and the rare steppenwolf.

Nevertheless, it is time to departure from this image and leaves it to the history books. When the sun rises above the Aral Sea today, it not only illuminates the skeletons of the once-so-great vessels in the “ship graveyard” outside the village Zhalanash, where silence reaches an elevation of almost religious dimensions – it also, only some 30 km. away, sheds light on a mosaic of small boats with busy engines, carving across the coastal zone of the Northern Aral Sea (hereafter: NAS) to tend the nets, which have been put out the day before.

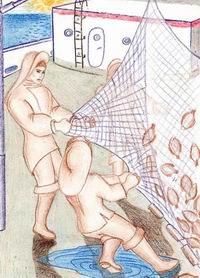

From camps on the sea shore in places near Tastubek, Akespe, Akbasty, Karateren, and Bugun, Aral fishermen are going out in teams of two-three, each team employing typically an eight-meter fibre glass boat, one engine, some twenty staying nets and already well acquired skills to take out and take care of the 200-500 kg. of flounder, they will probably catch. Setting the course for the future fishery on the NAS, one must be well aware of this new situation: the fishery industry today consists in a manifold of minor boats, small independent cooperatives, family brigades, and a variety of means for transportation. They say it is difficult to change the course of a super tanker; well here, the tanker is indeed stranded, and the course to be taken must take seriously into consideration that it is a flexible, diversified and decentralized fishery structure – a mosaic rather than a still-life – which it must fit. This mosaic will be described in more detail in chapter 2, and readers familiar with the fate of the Aral Sea and the history of the NAS fishery might proceed directly to that chapter. Here at first, we will dwell at the background of the current situation.

The rise and fall of the Aralrybprom

“…Sacrifice, dear comrades, Aral fishermen and workers, with a generous hand! By this you will not only do a real human deed, but also strengthen the workers’ revolution…”

V.I. Lenin, October 1921.

The fishermen in Aralsk were on a friendly basis with the first leader of the Soviet Union, Vladimir Ilich Lenin. Entering the union with much energy, and a helping hand for the victims of the civil war and the accompanying hunger across the union, the Aral fishermen won both fame and recognition for their efforts. The 14 wagons of fish that were given on Lenin’s request as emergency aid in 1921, were much appreciated by the Kremlin, and the letter of gratitude from Lenin still (in 2003) meets the visitor, engraved in stone on the central square in Aralsk.

The systematization and improving infra structure in the USSR had a positive impact to the fishery on the Aral Sea. While in 1905, fishermen along the coast of the Northern parts of the sea caught an estimated 660 tons of fish, already in 1925 this figure was tripled. On the 21st of October that year, the fish factory Aralgosrybtrest (“Aral State Fish Enterprise”) was founded, and the following years the plant was rapidly growing, with constructions of offices, works shops, lodgings for fishermen, etc. In 1933, the production of the fish factory had reached 12,000 tons. The factory was well established and perpetually expanding, and its progress continued until the dramatic alterations of the river flow and the marine environment set in the late sixties. The steady progress in the NAS fishery was only interrupted, in the late thirties and throughout the forties, due to the aftermath of the hunger catastrophe and collectivisation, which were especially harsh to Kazakhstan, and due to the war. During World War II, the Aral fishermen again donated much of their work for the common good – this time mainly to the Red Army – under the slogan “More fish to the front and to the country!” (From 1941-1945, more than 50,000 tons were given to the state) While many villagers were sent to the front themselves, the remaining workers and fishermen were kept busy providing victuals for the region as well as for “front and country”. Once the war was over, it took some time to normalize the production, but soon the catches again increased. In the five years’ plan of 1956-1960, which might be termed the peak of the Aral fish factory, the plan was more than fulfilled with an average of more than 20,000 tons/year, caught and processed under the auspices of the enterprise now renamed Aralrybprom (“Aral Fish Industry”). At the time, some three thousand fishermen, workers, managers and others were employed in the fishery industry of the NAS alone. Adding to this the spill over effects on practically all other fields of the society, the value of such an industry in a region with a total of 63,000 inhabitants (as of 1.1.1967) can hardly be overestimated.

Until the early 1970s, a variety of species such as carp, bream, roach, pike-perch, and sturgeon were caught in the sea, and processed in the Aralrybprom. The catches would usually be organized in such a way that a number of smaller vessels would do the actual catching and then hand over the fish to large mother ships, where cooling and primary treatment would take place before and during transport to the harbour in Aralsk. A developing processing industry provided the Soviet market with fresh, frozen, salted, and smoked fish, and the economy of the villages was flourishing in the post-war years. Soon however, all of these species were to disappear from the sea, and some of them even to be extinct – due to the irrigation of the Central Asian steppe and desert regions.

The Soviet Union, and in particular its 1954-1964 leader Nikita Khrushchev, found an enormous potential for agricultural production in the abundant rivers Amu-Darya and Syr-Darya, which run across most of the territory of the five republics of Central Asia, ending in the Aral Sea with evaporation into the atmosphere as the only outlet. With an average annual flow of ca. 56 km3, the two rivers represented a resource of such dimensions that it for many decades had kept Russian and Soviet engineers dreaming of a more efficient exploitation of it[1][1]. Already in 1882, the Russian geographer and climatologist A.I. Voeikov wrote: “The existence of the Aral Sea within its present limits is evidence of our backwardness and our inability to make use of such amounts of flowing water and fertile silt, which the Amu and Syr rivers carry. In our country, which is able to use the gifts of nature, the Aral Sea would serve to receive water in winter [when it is not needed for irrigation] and release it in summer during high flow”[2][2]. This “backwardness” was going to be compensated dramatically, when the “Virgin Lands” project was carried out. Beginning with the 1946 decree “On the Plan and Measures Concerning the Rehabilitation and Further Increase of Cotton-Growing in Uzbekistan for the period of 1946-53”, the central authorities made the steppe land of Central Asia a corner stone in the ambitions to reach self-sufficiency, which became strategically crucial after the war.

Agriculture in Central Asia was collectivized and industrialized, and the flowing water in the rivers was finally put to use. The production of cotton grew dramatically, and millions were employed. The Soviet cotton production went from 2.2 million tons in 1940 to 9.1 million tons in 1980 (5.5. million tons of which were produced in Uzbekistan). Being of course highly valuable, both economically and strategically, this production however proved to be extremely unsustainable. Firstly, the irrigated steppe and desert areas were relatively quickly exhausted (because of evaporation and mineralization), and mechanical and chemical initiatives notwithstanding, the production decreased from the 1980-peak to a level in 2000, which resembled that of 1960. Travelling across the Aral Sea basin by plane or train today, it is easy to detect symptoms of this development: vast white unused fields remind the traveller of an over intensified agriculture. How dramatic the set backs in cotton, wheat, and rice production will eventually prove to be, and how much this will mean for the balance of an imagined total economy of the “Virgin Lands” project (including the costs following from the drying out of Aral), it is not our intention to estimate[3][3]. Secondly however, the irrigation program meant a world of difference to the Aral Sea, and hence to the climate of a significant part of the region, and in particular of course to the fishery. The river flow went down from 56 km3/year in 1960 to a little more than 4 km3/year just some 20 years later, resulting in a sea level lowered by one third, the area of the sea shrunk to the half, and the volume of the water in the sea lowered by more than two thirds. As the balance between fresh water inflow and evaporation was impaired, the salinity grew dramatically – from lake level to ocean level in ca. 20 years. Entire ecosystems were changed. The flora and fauna around the sea were impoverished, reed fields were lost, the sand and salts from the bare, former sea bed were carried by the wind at huge distances, causing illnesses in the local area, and affecting even quite remote regions, and of course the marine ecosystem was dramatically altered: A significant number of species from all animal communities in the sea disappeared because of the increasing salinity. Many links in the food chain of the fish were heavily damaged; spawning areas for fish were drying out. For the fishery, this had disastrous consequences. The rich fish resources were all but extinguished from the sea, and the basis of the single most important trade in the Aral region was demolished. The water withdrew from the harbour in Aralsk, and channels had to be dug to keep boats from stranding. As from 1975, the fishery on Aral lost its commercial significance. Around this time, the efforts to maintain access to the open sea for the biggest vessels were given up. In Aralsk, a number of boats were left on the bottom of the harbour with no escape possible, and in the last port of refuge outside the village Zhalanash, the “ship graveyard” was a reality, when an attempt to dam water for the channel connecting the sea with the natural lake near the village, was irreparably broken[4][4].

For the Aralrybprom, this development meant a thorough restructuring of the enterprise. The deliveries from the local sea came to a complete stop, and fish had to be transported to the factory from other fishing grounds, in order to keep it working. The technical skills of the employees, as well as the physical infra structure of the plant, and its convenient placement on the Moscow-Tashkent railroad, of course still represented a big value to the union, and so a new line of production was introduced. As from 1980, the Aralrybprom received its fish mainly from distant Soviet fishing centres – like the Baltic countries, Murmansk, and even Vladivostok. Every day, four wagons of cooled fish would arrive to Aralsk by train, be processed there, and send back to the consumers all over the union. This kept the factory in business throughout the eighties, but with the perestroika and the following dissolution of the union, also these deliveries came to an end. The Aral fishermen meanwhile, were sent out to other lakes in Kazakhstan, and for 5-7 years, the fish from these places (especially the Balkhas Lake in Eastern Kazakhstan), together with catches from the delta-area of the Syr Darya, made out the raw material of the plant. By the mid-nineties, when local fishing communities, e.g. in Balkhas, had more than enough problems to supply themselves, most of the opportunities to catch fish in remote lakes were also closed, and in 1996, the situation in the NAS fishery was roughly this: The only fish in circulation was the fish caught in the fresh water lakes in the delta-area of the Syr Darya, and in the river itself. Practically, the fishery industry was non existent in the Aral region.

In 1997 nevertheless, the Aralrybprom, like countless other sovkhoz in the republics of the former Soviet Union, was privatized. Purchased by the private company Alem Zholdyzy, the heart of the Northern Aral fishery industry was divided into a number of sub-plants, which were rapidly bereft of most of their values. One by one they went bankrupt, and in 1999 all work was stopped – the short life of the new fish treatment workshop “Kyzmet” (the sub-plant containing the processing facilities of the former Aralrybprom) ending formally in 2000. The workers of the once proud and highly productive fish processing plant were finally “set free”[5][5], and today, the only signs of the many years of more than fulfilled production plans, are the open bare ground, where workshops, offices, laboratories, etc. were situated, and the one last lonely building with the skeleton of the former freezing facilities and cold storages.

Although however, the last thirty years of the Aralrybprom was in fact a continuous decline in nearly every aspect, the employees of the factory nevertheless were able to mobilize the last efforts of the enterprise to contribute to the initiation of a new fishery, which would prove to give back the hope to the Aral fishermen, and re-establish the NAS as a valuable commercial fishing ground.

Pleased to meet you – introducing the flounder, the international cooperation and the new structures in the fishery.

The history of the Aral Sea is adverse. The river flow of the sea’s two lifelines has varied, and droughts have been registered earlier, incl. such caused by human influence. What make the events of the second half of the twentieth century remarkable and catastrophic is of course the immense and unforeseen effects they had on the lives of millions of people, especially in the Aralsk and Muynak regions. In much the same way, the fate of the many species of fish that disappeared from the sea, is not in itself a tragic story, but certainly the consequences their disappearance had to the lives of the people around the sea. These seemingly trivial remarks should emphasize the following. To understand the current situation in the NAS fishery, it is needed to understand that the ecological catastrophe of the drought and the damaged ecosystems is not a destruction of an original or pure natural environment without artificial components. The Aral Sea was already before the present crisis highly influenced by human interaction, and especially its ichthyologic history is rather complex. The biological science in the USSR was always an industrious one, and ichthyologic expertise was employed already from 1927 to introduce alien species to Aral. Species such as sturgeon, shad, mullet, shrimp, herring, and carp were introduced during the build up of the fishing industry around Aral, and the marine environment was carefully monitored – new plans of breeding and introduction always on the way. It was therefore no sudden revelation that made Soviet scientists come up with the idea to introduce new species to Aral, when the rising salinity made it seriously difficult to maintain the animal communities from the brackish water ecosystem. Along with other species (mainly those in their food chains) the snakehead and one flatfish – the flounder Platichthys flesus – were introduced in the years around 1979. Like both indigenous and other introduced species, these new members of the Aral marine community were carefully followed by the KazNIIRX institute in Aralsk[6][6]. The Platichthys flesus – or in Russian Kambala glossa, was introduced from the Azov Sea, and was particularly well fit to the varying conditions in the Aral Sea, especially with regards to the salinity. Needing a minimum of 12-14 mg salt/l to reproduce, and being able to survive in even extreme conditions (an expedition to the Southern Aral Sea in 1998 showed that Kambala in abundant numbers were living well in salinities of up to 60 mg/l), the flounder soon proved to be the right choice for maintaining fish life in the sea. Around 1990, the ichthyologists of KazNIIRX in Aralsk found it appropriate to initiate a trial fishery for flounder to see if their prognosis would be sustained: That the flounder could be the new commercial species in Aral. One of the most distinguished fishermen in the region, mr. Nargali Demeyuv, was appointed to head a brigade and conduct the trial fishery in the spring of 1991, but even though the catches indicated that the potential might be real, the conditions in nearly all fields of organization, hardware, treatment, and distribution made it a potential which could still not be actualized. In short, the Aral fishermen needed new equipment (the seines used were unfit for catching flatfish, and they had not been renewed for quite some years), and knowledge of the handling of the new fish. Furthermore, the people in the region were entirely unfamiliar with flatfish, and in effect not counting it as a fish fit for consumption. The flounder fishing therefore was stopped again before it really got started, and like in many other fields of the society, initiatives and optimism were fading. The inhabitants of the Aral region grew increasingly accustomed to a victim identity: They were the ones who lost in the great game of the Virgin Lands, and while many people emigrated from the region, the remaining were depending more and more on public welfare and subsidies from the state (most salaries in the nineties were added an “ecological compensation”, as the Aral region was considered an area of ecological disaster.) After 20 years of withdrawal of the coastline of the sea, the fishery was maintained merely in the songs about the proud past, and in the tales, which the aksakals could entertain with on the long winter evenings. A generation of youngsters grew up without even seeing the sea, which was the background of their cultural identity. This was the situation, when the idea was born to create a Danish-Kazakhstani cooperation.

In 1994, Danish fisherman and environment activist Kurt B. Christensen decided to invite two colleagues, an ethnographer and a photographer, on a trip to the Aral Sea. Having visited the region on one occasion earlier, Kurt couldn’t free himself from the image of the iron corpses in the ship graveyard, now situated tens of kilometres away from the sea. The three set out with the purpose of telling the story of the ecological catastrophe through the eyes of the fishermen, who had experienced it first hand. Until now, the story of Aral was mainly known in international media as the story of the irrigation project, the dramatically shrinking sea, and the sands and salts blowing just about everywhere, but not so much as the story about the professional fishermen who were overheard and put completely out of business. On this trip, in the village Zhalanash, just two-three kilometres away from the stranded vessels on the former sea bed, a Soviet book from the 1930s should come to play a surprising role. Then bookkeeper of the Djambul fishery kolkhoz, Tolagai Ualiev, was hosting the visitors from the far West, when he suddenly reminded the book. Talks had been on a variety of subjects, and the company was about ready to turn in after another day filled with impressions and warm meetings, when mr. Ualiev went to his bookshelf and took down the 1939 edition of Teoriya i Raschet Orudij Rybolovstva (Theory and Estimation of Fishing Tools), which contains a paragraph on Danish seine fishing for flounder. In this paragraph, the “theory of catching with Danish seine” is described, with references to the inventor of this technique in 1848, Danish fisherman Jens Væver. Having recollected old days and discussed the perspectives for the fishery industry in Aralsk with the Danish guests, Tolagai Ualiev came up with an idea. “If you want to do something concrete here, except from telling our story – why not to investigate the possibilities to employ the Danish techniques of flatfish catching in Aral?” Being somewhat surprised that there was even fish in the sea; the Danish group agreed that the idea in principle seemed immediately obvious, and went home determined to investigate the possibilities of an initiative. Contacts were maintained between Denmark and Kazakhstan, and in 1995, a group of five people with connections to the Kazakhstani fishery industry visited Denmark: The chairman of the Djambul kolkhoz, the deputy mayor of Aral region, the last general director of the Aralrybprom, the leader of the Balkhas Fishery Research Institute, and the Kazakh coordinator of the new international cooperation. In Denmark, meetings were held with potential donors, and the Kazakhstani group got acquainted with the Danish fishery industry. A “Protocol of Our Common Aims” was signed, and in 1996 the idea from the late night dinner table in Djambul came into actual being.

Danida (The Danish Development Agency) funded the first phase of the fishery project “From Kattegat to Aral Sea”, which mainly consisted in a trial fishery on the Aral Sea in October 1996. Prior to this, a group of 19 people from the Aral region and Almaty (then capital of Kazakhstan) – fishermen, technicians, scientists and translators, visited Denmark to create a common background for the coming partnership, and for the fishermen specifically to work with flounder fishing on board Danish cutters. A truck arrived to Aralsk from Denmark at September 22 with 1,000 nets for flounder catching, warm clothes for the autumn and winter seasons, other fishing tackle, and some presents for children in the local schools. And beginning on the 2nd of October, 63 Aral fishermen from the remains of the Aralrybprom, plus the two kolkhozes still in business at the time (“Djambul” and “Raim”), together with four colleagues from Denmark, conducted a trial fishery from the sea shore outside the village Tastubek, hoping that the catches during the 14 days period would make it feasible to continue the fishery project and eventually re-establish a fishery on Aral. Preparations were made in an atmosphere mixed of excitement and speculation: What did these Westerners really want? In some places, suspicion was more prevailing than willingness to co-operate, and the foundation of the project was therefore not to be laid in the many discussions and signatures, but in the concrete, practical work among colleagues. Kazakh and Danish fishermen found each other in the shared wish to take part in the historic event of a re-establishing of the fishery on Aral. Most of the work was conducted with a common tacit understanding of the craft, and for more abstract discussions schoolteachers were volunteering to work as translators on the shore and on the sea. Evenings were spent in the village with discussions, story telling, singing and joking, and on the night before the first nets were put out, a group of retired fishermen with experience from the great fisheries of the 1950s and 1960s visited the camp to pray for a successful common job. Besides the obvious need of a sufficient amount of fish, there was also the quality of the flounder to consider: Was it at all fit for human consumption (or containing too many heavy metals, pesticides, or other contaminators from industry and agriculture), and was it of a gastronomic quality that would enable the fishermen to create a market for it at all? The answers to these questions were overwhelmingly positive. Employing only about two thirds of the nets brought in from Denmark, and small eight-meter fibre glass boats, many of which were build for fishing on the river, the Aral fishermen landed more than 50,000 kg. of flounder during a fortnight. Notably, the quality of this fish was outstanding. Laboratory tests proved that contamination was not a problem, and the fish itself was delicious and of much higher quality than e.g. Danish flounder (more like a plaice).

These encouraging results were to make out the foundation of the fishery project, which is now (2003) entering its last year. While Danida remained the main sponsor throughout this period, private companies, foundations and individual fishermen in Denmark also contributed with hardware and labour to the project, and in the Aral region, volunteers supported the idea from the beginning, and became more in numbers for each passing year. The thought of reviving the Aral Sea fishery was compelling, and nearly every person in the region had relatives or friends who had worked in the fishing industry, if he or she had not him-/herself been employed as a fisherman or at the Aralrybprom. Cooperation between Denmark and Kazakhstan was conducted initially through the two main coordinators: Almaty biologist and associated professor Makhambet M. Tairov in Kazakhstan, and Kurt B. Christensen in Denmark, but in 1998, the volunteers in Aralsk, together with the growing numbers of fishermen, founded the NGO Aral Tenizi, which eventually became responsible partner of the Danish Society For a Living Sea.

The fishermen themselves were initially organized in the old Soviet structures: The majority still under the auspices of the Aralrybprom, and a considerable part in the two remaining kolkhozes, Djambul and Raim. As the branches of the Aralrybprom began to go bankrupt however, the fishermen from the villages, which had been sorting directly under the sovkhoz, began to take initiatives to become more independent. The catches from the trial fishery in October 1996 meant a sudden revival of the fishing industry. Already during the winter season 1996-97, local groups of fishermen decided to continue fishing on their own hand – and with good results. In 1997, the fishery project encouraged and supported the fishermen to create new independent cooperatives with a maximum of 15 members, in agreement with a reform in Kazakhstani regulation on private enterprise. The new cooperatives became juridical bodies and obtained the possibility to enter concrete and binding agreements with the fishery project. This has since 1997 meant that an increasing number of fishermen have received administrative, professional, and hardware support from the project, and that today some 90 brigades (ca. 600 fishermen) have been equipped to catch fish on Aral again. Accordingly, the catches have gone up. The 20 years of stand still were ended in 1996, when ca. 150 tons were caught and only minor set backs due to storms, ice, etc. have broken the progress since then.

Since 1996, Danish delegates have visited the Aral region every year. In all, 18 Danish participants have worked in the region, incl. first of all fishermen, one biologist, technicians, NGO consultants, students, journalists and photographers. The total amount of work reaches approximately five man-years (not counting the volunteer work in Denmark). Most of this work has been focused on the handling of the transportation and division of fishing tackle from Denmark and on the build-up of the co-operatives and the NGO, and each year since 1999, Danish representatives have been present on the general assembly of Aral Tenizi. The division of responsibilities between Danish and Kazakh partners has moved in direction of local involvement and authority. Depending heavily on the two outside co-ordinators (from Almaty and Denmark) in the first couple of years, the Aral fishermen and civil society have increasingly taken responsibility.

A number of heterogenic factors made it possible to re-establish the fishery on Aral: The flounder, which had had a little less than 20 years to adjust to the environment in Aral, the encounter – right on time – of the Danish and Kazakh fishermen and their cooperation in the project “From Kattegat to Aral Sea”, the readiness of the fishermen to establish new structures and adopt a new kind of fishery, and the capability of the civil society in the Aral region to grasp the opportunity to support the positive development with volunteer- and eventually also professional NGO work. After a couple of years of common efforts, the result was clear: There was a real potential for a revival of the commercial fishing on the NAS.

Methods and results of the fishery project “From Kattegat to Aral Sea”.

As indicated, the revival of the NAS fishery depended on a number of factors. The successful acclimatization of the flounder to the saline waters of the shrunk Aral Sea evidently was a sine qua non. Furthermore, the efforts to establish new and sustainable structures in the fishery industry of the Aral region have depended on a close cooperation between Kazakh and Danish fishermen, and a high degree of faith in the common aims and intentions. In fact it is our claim that the development in the fishery industry of the NAS would have been impossible with a traditional development/aid – approach. The direct and engaged involvement of the Aral fishermen themselves has been the engine of the project; not only did the original idea of the project spring from a fishing kolkhoz, the fishermen have taken part in discussions on each step of the development, first of all through the board of the society Aral Tenizi, which has been responsible partner and distributor of communication and equipment since 1999. In a profound sense of the word, this project has therefore been a grass root-project. Literally, the raw material for the project has been lifted up from the sea, and the entire project has been founded on the common practical work of Kazakh and Danish fishermen, initially in the 1996 trial fishery from Tastubek at the North-West coast of the NAS. The importance of this situation for the future efforts in further developing of the NAS fishery should not be underestimated: The NAS fishermen have taken up the challenge to re-establish their trade as a viable and sustainable business, and they will demand to be heard in future vital decisions on their field. Their organization in new fishery cooperatives, the establishing of new structures in the treatment and selling of fish, and the common decisions and voice in the NGO Aral Tenizi, have all been supported by the project “From Kattegat to Aral Sea”, but the real strength of this project has been the motivation and involvement of the people involved in all chains of the production, from sea to table.

The common work of the Danish delegates and the staff and board of NGO Aral Tenizi has been to encourage, support and monitor viable initiatives in the NAS fishery. This has demanded much creativity, patience and persistence from all involved parties, and the methods have on each step been to include and join forces with everyone, who supports the purpose of the project. The project has therefore taken part in so different things as repairing fibre glass boats, packing frozen fish in boxes, cooking advertisement meals on the central square, arranging contests for school children’s drawings, searching for buyers in bigger cities, having meetings with regional and national authorities, catching fish, eating traditional meals, publishing a book on the most honourable fisherman of the region, arranging seminars and assemblies, giving credits and monitoring the appliance with the contracts…

Beginning with the visit of the leaders of the (remainders of) the NAS fishery to Denmark in 1995, the fishery project build on an ever extended directness in the cooperation between the parties. The agreements made in 1995 were effectuated in 1996, where firstly a group of NAS fishermen visited Denmark and got a grip of the Danish traditions of flounder fishing, while at the same time drawing a sketch of the cooperation to be carried out in the October trial fishery, and secondly the actual fishing from Tastubek village was conducted with a very limited material affluence, but a high level of engagement and professional comradeship. The interdependency in the quest for a successful trial fishery created a bond between the Danish and Kazakh partners, which has tied the common work together through many difficulties since then. Going to the sea, clenching the fish, weighing and transporting, negotiating prices with potential buyers, keeping in touch with ichthyologic expertise and with the local authorities – all these activities have had a double sided effect:

- The NAS fishermen have obtained a significant degree of independence and self-sufficiency. Being regular employees throughout the period of the USSR, with a very limited responsibility (in scope), the fishermen have been depending on outside organization of practically all parts of their trade, except of the actual catching of the fish. This dependency has been, and still is, one of the major difficulties in the project. Now however, the cooperatives, the private initiatives in fish treatment, and the common voice of the fishermen in Aral Tenizi, have reached a level where no return is possible. Any future development of the fishery industry of the NAS must take this into account: Decentralized and inclusive methods and solutions are essential for a continuation of the virtuous circle.

- The NGO workers and the volunteers on both Danish and Kazakh side have obtained a practical experience which makes them highly competent in dealing with problems in all links of the fishery industry which will now be build around the NAS. Depending from the very beginning on four Danish grass root workers, and the volunteer efforts of the Aral region civil society, the people involved in this process have had to make decisions in fields far beyond their immediate scope. School teachers and their students, unemployed volunteers, and most importantly former employees of the Aralrybprom have taken part in this development on each step. Along the way, novel ideas and experiments were created in order to overcome the difficulties on practically all levels, from how many fishermen should be in each brigade to receive support or credits, over hygienic standards in transporting and washing the fish, to marketing in local cafés and at big city markets. Any future development program for the NAS fishery will have the unique advantage of an easily attainable bank of knowledge, experience and know-how on any imaginable field – it is all available in and through the NGO Aral Tenizi, and the village branches of this society.

Concretely, the fishery project has developed along the following phases:

Preparation

1994: The idea of the project is born in the village Zhalanash during a visit of a Danish delegation.

1995: A delegation of fishery leaders, scientists and the deputy mayor of Aral region visit Denmark to elaborate the ideas and make preliminary agreements.

First phase of the fishery project: Trial fishery

1996: A group of fishermen from Aralsk visit Denmark for a one month study of Danish NGO work and flounder fishing. Agreements are made on the October trial fishery.

A cargo of 1,000 nets and other material arrives from Denmark to Aralsk, and the trial fishery from Tastubek is carried out with remarkable results. NAS fishermen continue catching flounder throughout the winter season.

Transitional phase: Developing sustainable structures

1997: New legislation in Kazakhstan encourages the establishing of smaller private cooperatives. The fishery project supports the NAS fishermen in this procedure.

1998: During the autumn fishery season, the project makes its first attempt at promoting a correct treatment of the flounder “from sea to table”. 23,000 kg. are treated according to European standard and sold on the market, mainly in Almaty.

A biological expedition with Danish and Kazakh scientists investigates the condition of the flounder in both the NAS and the SAS.

The NGO Aral Tenizi is founded.

The last phase of the fishery project: Sustaining the virtuous circle

1999: Aral Tenizi celebrates its first general assembly.

The second cargo of equipment from Denmark arrives. The (refrigerator) container itself becomes the first step in establishing local receiving stations near the fishing grounds around the NAS.

A minor credit scheme is established within the frames of Aral Tenizi to enable micro credits to be available for fishery cooperatives.

A Norwegian TV-group shoots the first documentary on the new development in the NAS fishery: “The dream about the great catches.”

2000: Two more containers from Denmark arrive.

Another promotion campaign for the Aral flounder is conducted within the auspices of the fishery project – this time treating 140,000 kg. in cooperation with the factory Aknur.

2001: One more container arrives. The receiving stations are beginning to function. The fish processing plant Karasai Kazi obtains right to utilize the new container for one year, in return for assistance in receiving the cargo from Denmark.

2002: The last of the five containers transported from Denmark until present day arrives in Aralsk. Receiving stations are now built up in Akbasty, Tastubek, Bugun, and Karateren. A third processing plant emerges in Aralsk: Akbidai-2. However, even with three enterprises in function, abundant catches in September and October result in serious difficulties in handling the fish accurately, which again leads to a low average quality and reduced prices.

2003: Investigations are made of the possibilities to strengthen the freezing and processing links in Aralsk. Preparations are made for establishing a new type of organization in Aralsk. Common meetings among fishermen and NGO employees result in a decision to opt for a reworking of the procedures in treating the fish – ideally in a new plant owned and controlled by the fishermen themselves through Aral Tenizi.

Figure 2: Flounder catches from the Northern Aral Sea, 1994-2002 (tons).

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

|

0 |

0 |

165 |

350 |

200 |

250 |

500 |

800 |

1000 |

Sources: Ermakhanov, Aral Tenizi.

The results of the common efforts of the Kazakh and Danish fishermen during the past decade have many facets, and involve literally thousands of people all around the NAS. A more detailed picture of the situation six years after the common trial fishery in 1996 can be found in the following chapter, but let us here illustrate some of the impact of the re-establishing of the fishery by focusing on two stories, concerning the development of one family and one village: Kanaly Kanibetovs family in the village Zhalanash, and the fishing village Tastubek.

Kanaly Kanibetov and the cooperative “Asta”.

In 1998, the fishery project was busy initiating a controlled experiment to treat and sell flounder according to European standards. As described above, in event 23,000 kg. were treated and packed and sold with nice results for all involved parties. At the same time, negotiations were perpetually going on between the Danish delegates, their partners (volunteers) in Aralsk, and the ever increasing amount of fishermen from all over the region, who came to the city because of the rumours that one Danish project was giving support for fishery. Among the many applicants for support were also some opportunists with very unclear intentions of anything except gaining from the benefits of international aid, and of course a number of people who were genuinely interested in the possibilities to use the fishery project to start something new and valuable, but without credible means to realize these intentions. The project workers were therefore carefully making interviews and discussing internally each candidate to make sure that the equipment and eventual credits were given out for a worthy purpose. The procedure (as it was maintained and developed throughout the project period) was a detailed interview combined with a thorough discussion between the Danish and Kazakh NGOs (i.e. from 1999 between Living Sea representatives and Aral Tenizi staff): Do we know this person, is he or she really a professional fisherman, is the information stated in the interview liable to be true and the plans realistic, etc. Among the criteria were that the cooperative should be registered, boats and vehicles should already be available to the fishermen and clear and realistic intentions to catch fish from the sea itself (and not from the stressed ecosystems in the delta-area) should be discernable. One of the people, who came to Aralsk in the autumn of 1998 with nothing much but good intentions to offer, was Kanaly Kanibetov. A genuine pater familias, Kanibetov wanted his family to take advantage of the one positive development in the region, he knew of: the fishery. Therefore he came to the headquarters of the fishery project and stated his intentions. He wanted to catch fish from Aral, and asked for support. On the face of it, there was no reason to suppose that Kanibetov could fulfil the criteria to receive support: All questions about the available gear, which the project demanded, were answered negatively. No boats, no vehicles, no nets. Kanibetov however saw no problem in this. “I have adult sons”, he said, ”and I will take them with me to the sea. There, we will undress, and drag the nets, which we will borrow from the project, and place them in the sea. The fish we catch will be the basis of our fishery cooperative.” The insisting look on Kanibetovs face made the project workers hesitate to decline him assistance, and after some consideration they agreed to provide him with the immediately necessary means to start fishing. The cooperative “Asta” was soon founded, and Kanibetov did as he had said. Fish was caught, eaten and sold, and some income was generated, whilst – economically equally important – the expenses for buying meat were lowered. In the following years, “Asta” expanded its activities, and today all Kanibetovs seven sons, and partly his four daughters, are living from the fishery. The cooperative is one of the best examples of the driving forces in the work to re-establish fishery on the NAS: Determination, willingness to cooperate with all involved parties (NGOs, juridical and political authorities, fish processing plants, relatives…), and trust in the common understanding, the handshake and the goals that transcend the immediate hit-and-run profit seeking. Today, Kanibetovs family takes part in the common work to re-establish the fishery on the NAS, they vote at the general assembly of Aral Tenizi, and they catch fish. Fish is distributed within all the links of the family, and the surplus sold through the plants in Aralsk. This business has generated enough profit for Kanibetov to enable him to buy four vehicles, incl. one truck.

The village Tastubek.

Another story, which during the project period of “From Kattegat to Aral Sea” has been central to especially the Danish participants, is the story of the village Tastubek. As described above, it was on the shore near Tastubek that the 1996 trial fishery was conducted. At that time, the village consisted in a mere six-seven houses with the families, which more and more seemed to have simply postponed the inevitable: To leave the remainders of the once affluent and highly productive fishery community and move to Aralsk, or to Saksaulsk – another nearby town. The families were living from the pensions of the elderly, and the scarce profit from some meat production and the zhubat (camel’s milk), which is especially rich in Tastubek. On the shore itself, no traces of human activities were visible for miles in all directions. The yurtas (nomadic tents) and the one wagon, which were placed there to make out the headquarters of the fishery project, looked slightly misplaced, when the nets were put for the first attempts. During the successful period of the trial fishery however, life rapidly returned to the shore: The overwhelming amounts of fish, the birdlife accompanying the vessels already in the second week, the many languages spoken (Kazak, Russian, English and Danish), and the trucks that increased in numbers as it dawned on the leaders of the Aralrybprom that there was more to the attempt than valuable equipment from the West – there was fish, a lot of it, and of high quality. After the Danish project workers had long gone home to their families, studies and jobs, the fishermen in and around Tastubek continued investigating the possibilities to make a decent living from catching fish. With organizational structures in a state of disintegration (the new cooperatives were only to be encouraged by the government the following year), private people tried their luck at catching fish for their own consumption and some micro trade in the villages. For Tastubek, these modest beginnings meant a world of difference. During the winter of 1996/97, the villagers worked industriously to sustain the positive results of the trial fishery, and to make a real try at reviving their trade. Even though marketing was naturally low, if not non-existing, and the fishing had to be conducted with fragile old local nets (the kolkhozes and the Aralrybprom were still responsible of all Danish nets, which had been brought in), the winter showed that there was real perspective in the flounder fishery, and Tastubek was among the first to register a cooperative, when the new legislation was ready. Year by year, the fishermen of Tastubek improved their situation. They borrowed nets from the project, obtained credits, and they organized their own catching and selling. Some of the families that had left the place recently returned, and eventually even people from outside came and build houses. Almat Aitbaev, for instance, moved out from Tastubek with his parents in 1972. Almats father received a job as a driver in Aralsk, and Almat himself followed in his father’s steps, until the House of Culture, where he was employed, had to annul his job due to economic reasons. He then found a short engagement in the Aralrybprom (send out as a fisherman to the Irgiz lake near Aktobe), but only to see this opportunity also coming to an end. When his brother Dusbai – who had stayed in Tastubek – told him about the new possibilities in the village, it was therefore logical to Almat to try his luck and move back to the village, which he did in the summer 2000. One year later, he was so convinced of the reasonableness of his brother’s words that he started building his own house, and today the brothers have even opened the second fishery cooperative of the village – “Aibolat DAE”, counting six fishermen.

The streets of Tastubek are now again described in the plural, and more than 20 houses are making out a solid foundation of a new period of optimism. Among the innovations in the village are also the receiving station, which is structured around one of the cooling containers send from Denmark, several houses build by fishermen from outside for season accommodation, and a brand new school, build by the villagers themselves, and employing a teacher for the two classes already busy learning (just two years ago, children had to move to Zhalanash, Aralsk or Saksaulsk, if they were to receive education – not all did).

Economical progress and environmental action.

It is beyond any doubt that the re-establishing of the NAS fishery has had a number of positive effects. The income of up to 600 fishermen and their families has been lifted, and in some cases even boosted. The basis for an interesting, though in global scale of cause modest, industry has been established. And the democratic development of the Aral region has been supported through the involvement of the fishermen, the NGO mobilisation, etc. However, a basic question has been underlying the whole enterprise from the beginning: What if the dark prognosis will prove true and the sea will entirely disappear? Wouldn’t all these efforts have been wasted and people been given false aspirations? An answer could be given along these lines.

It is the official policy of the Danish Society for a Living Sea that the protection of the marine environment must take place with the direct involvement of the parties most immediately concerned, which in most cases means the fishermen. A sustainable management of the natural resources can only be made realistic, if it is conducted in accordance with, and at best by the users. Therefore, the role of the grass root project in Aralsk has not only been to provide people with gear and a temporary income, but also to join forces in the efforts to make the outside world aware of the potentials in preserving the sea as a source of economic growth and climatic stabilisation. The many meetings with regional, national and international organisations have increasingly indicated the results of this work. First of all, the NGO Aral Tenizi is today broadly accepted as a trustworthy and perspective organisation, which is based on real and direct knowledge of the complex natural and social conditions in the NAS and its surroundings. Secondly, significant political decisions have been made during the past five years, which indicate a clear and positive will to fight for the remainders of the sea. It is difficult to say how much influence the events in Aralsk and the fishery communities of the NAS have had on these decisions, but whatever the motivations, they do give new hope for a sustainable development of the NAS fishery trade. In February 2002, the Kazakhstani government and the World Bank signed an agreement on the “Syr Darya Control And Northern Aral Sea”. This agreement aims directly at preserving the NAS – partly by repairing a line of sluices, channels, and other constructions, which for many years have caused an immense waste of water along the Syr Darya, and partly by building a dam across the Berg Strait between the NAS and the SAS. The dam construction has been tried at several occasions earlier on local initiative, and has proven to have very positive effects to the environment of both the NAS and its terrestrial surroundings. An improved and well prepared construction, based on earlier experience and external expertise, should enable a solid and lasting solution. The aim of a dam construction is shortly said to change the current situation, where most of the water from Syr Darya runs to vast shallow areas south of the Berg Strait, and mainly evaporates. According to the organisation responsible of the design of this project, the KazGiPoVodKhoz in Almaty, the planned construction should enable a stabilization of the water level in the NAS at 42 m. above sea level, by an annual flow of 3 km3 per year. (The tender has already been held, and won by the Russian construction company Sarubevodstroi. The construction work is scheduled to begin during 2003). This would have as an effect that the salinity would be significantly lowered (estimated at an average 17 mg/l. and at many places undoubtedly lower), and fresh water species would be introduced. The coast line would stop withdrawing, and instead take back deserted former sea bottom – even though the water will not still reach Aralsk (this would require a water level of 46 m.). The conditions for fishermen all around the NAS would be considerably improved, and the build-up in the NAS fishery industry, which has recently taken place, would prove to have been only the first small steps in a serious remaking. A sum of US$ 2 million has been earmarked in the World Bank project to support the fishery industry of the NAS. Hopefully, these and other investments will be realised in the coming years to the benefit of the communities of the Aral region.

Chapter 2: The NAS fishery – the situation 2002.

The story of the Aral Sea fishery as described in chapter 1 above is one of radical changes. The industrialization and centralization during the reign of the Soviet Union undoubtedly carried with it a number of advantages for the fishery industry. Production was steadily increased until the ecological set backs began. But the centralized administration and control of the fishery industry also meant that it was very difficult for the NAS fishermen to adjust to the new requirements, which were to follow from the novel ecological and economic situation around the time of the dissolution of the union. Therefore, the build up of sustainable new structures in the fishery industry required time, patience, determination – and outside support, as described above. This work has taken place for nearly a decade at present time, and the development has parted with some old structures, kept some of them, and created some new. In general, it can be said that a variety of decisions and initiatives have been re-located to demand more direct involvement of the fishermen, as well as from the managers of the fish treatment plants, and that this development offers both advantages and new challenges for those who wish to deal with fish from the NAS, or with the trade in general, be it as businessmen, project workers, or administrators. To anyone with an interest in the NAS fishery, it is imperative to be familiar with the basic structure within the fisheries today in order to navigate in the complex network of the industry. In this chapter we will therefore seek to give an instructive overview of the present situation, partly to draw “a map” of the actual state of affairs, and partly to thereby give the background for a number of suggestions for improvement, which will be summarized in chapter 3. The description will move from the sea to the table, from the resource to the market, and end with some comments on the role of NGOs.

The resource

As described above, the species composition in the Aral Sea has undergone many changes during the past century. A variety of fish has been introduced, many of which have again disappeared, and the ichthyologic expertise of the Soviet Union has had a significant influence on this development. In terms of ecological sustainability, it should therefore be emphasized that the flounder Kambala glossa is not a natural inhabitant of the environment, and that its disappearance would, if it should happen, not be a catastrophe – the damage would first of all be economical[7][7]. The management of the resource, which the flounder currently represents, must obviously be careful and take into consideration the recommendations for total allowable catches, which biological expertise can offer, but mainly in order to sustain the flounder as an important source of nutrition and income to the inhabitants of the region.

The monitoring of the stock is thus – especially for economical reasons – very important, and it is most advantageous that the former Soviet, now Kazakhstani ichthyologic institute KazNIIRX has followed the stock since the introduction in the late seventies. The Aralsk branch of the institute, headed by Tenstk Kulmaganbetov, and with biological leader Zauolkhan Ermakhanov, possesses valuable information on the development of the NAS flounder stock. It was the KazNIIRX, which encouraged the trial fisheries already in 1991 (see chapter 1 above), and it was also this institute, which supported fishermen and project workers with estimations of possible catches and optimal fishing grounds during the nineties. Due to the economic recession following the dissolution of the union, the financial situation of the institute has however been quite harsh in recent years. Employing at its peak more than 70 persons, the Aralsk institute today counts only 11 people, most of who are only part time employed, and the institute to a considerable extent depends on outside funding, e.g. in international projects. One of these has been the fishery project, which has been working closely together with the KazNIIRX branch in Aralsk since 1996. Another international cooperation is currently taking place to investigate a number of questions on the NAS ecosystem. A group of specialists, incl. Kazakh, Russian, French and Irish scientists, are – in an INTAS project – monitoring and describing the present situation, incl. the condition of the flounder stock. The following information is based on the preliminary results of these investigations, courtesy of the Kazakhstani biologists Makhambet Tairov and Zhanna Tairova from the INTAS project in collaboration with KazNIIRX, Aralsk.

Based on the biological monitoring, and a number of trial fisheries, the total biomass of the Kambala glossa in the NAS is estimated at 4,500 tons, as of September 2002. The scientists recommend that 30 % of the stock can be caught every year, without damaging the stock. This gives a total recommended catch per year of 1,350 tons. One of the interesting results of the recent investigations is that the stock in the NAS seems to have stabilised, when comparing to the results of investigations in 1998. In 1998, the population of Kambala glossa in the Southern Aral Sea was represented by five generations, and in the NAS only by three. The fact that the flounder population in the NAS is now represented by six generations indicates a stabilisation (similar data are characteristic of the Kambala glossa in the Azov Sea, which is the origin of this species). The flounder feeds mainly on the bivalve mollusc Syndosmia segmentum (71% of the mass from the stomach contents in analysed fish), and on the worm Nereis diversicolor (10%) and smaller fish (11%). Syndosmia and Nereis are abundant in the NAS, and have been for a number of years, and these species of zoo benthos are the main food basis for the Kambala. (Danish fishermen participating in the project are convinced that the high percentage of mollusc in the food composition of the flounder also accounts for its high gastronomic quality.) The condition of the zoo benthos is considered to be the main limiting factor for the productivity of the fish stock in the NAS, and therefore has an important value for the fishery planning. The investigations on the zoo benthos will be extended in the coming years.

As described above, the total catches of flounder have not exceeded 1,000 tons at any point, and accordingly leading ichthyologist at the KazNIIRX institute in Aralsk, Z. Ermakhanov, maintains that the catches might go up further, and that they even should, in order to optimize the conditions for the stock. Having said this however, it is also worth noticing that the statistics of the catches still depend to some extent on estimations, and that the actual numbers might be higher than indicated. Therefore, a careful biological monitoring will be very important in the coming years, as well as an effective and broadly accepted means to ensure that fishermen and salesmen are well informed about the state of the stocks, and about possible sanctions in case of misconduct.

The seemingly stable stock of flounder in the NAS represents an important value to the region. The recommended catches of 1,350 tons/year equals a total value of ca. $500,000. This represents no less than 10 % of the total budget of the region, (which is especially remarkable in the light of the fact that 60-70 % of the budget for a number of years have been given in the shape of government subsidies.) With a well-organised fishery industry and a transparent market structure, the region administration might come to benefit greatly from the trade again. Furthermore, two fields of quite radical improvements are still open: Firstly, the handling and processing of the fish might be improved significantly to heighten the price, maybe up to a doubling of the value, and secondly, the perspectives of a dam construction across the Berg Strait give hope of a very significant increase of the total allowable catches, incl. other species like the valuable pike perch.

The fishermen

The re-structuring of the fishery industry of the Aral region coincided with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and a line of forms of organization and conduct, which belonged to that era. As already stated, the break down of the Aralrybprom and its privatized descendant Kyzmet created an empty space at the very heart of the NAS fishery. The resulting transformation process has consequently been especially troublesome to the fishermen, brigades and workers, who were most closely linked to the sovkhoz (i.e. mainly fishermen in Aralsk, Karateren, Bugun, Amanotkel, Akespe, and the technicians and fishermen at the rybprom itself.). The outstanding debts, which were never paid to the local branches of the limited company formerly known as a sovkhoz, put the fishermen and the local leaders in the villages in an awkward situation. In some places, gear was divided among the fishermen to ensure some minimum of outcome from the old factory, in other places very significant sums and amounts of equipment were lost, because of the bankruptcy. All this meant that the independence of the fishermen was for a long time put into objective constraints. The willingness and ability to make the leap from employed worker in a centralized fishery industry to co-owner or active participant in an independent fishery cooperative was naturally delayed by this situation, and only recently have very strong co-operatives begun to function well in the places in question. A number of former and new leaders have had to take significant responsibility in the transition phase. In the kolkhozes, Djambul (roughly equalling the village Zhalanash) on the West side of the sea, and Raim on the East, things have gone considerably smoother. The common responsibility and direct local ownership made the transformation from kolkhozes to co-operatives less troublesome. In both places, fishermen have now re-organized themselves – some still in structures very similar to the old kolkhoz system (in the co-operatives “Djambul” and “Raim”) – others in co-operatives or private companies owned by one or a group of local fishermen.

The Kazakhstani legislation from 1997, which introduced the new conditions for private ownership, resulted in a lot of activity in the fishery project, and eventually in the office of the NGO Aral Tenizi. As the project continued after the successful trial fishery in 1996, a set of conditions were developed to ensure that equipment and credits were given to independent, sustainable and trustable persons. The main evidence of this status was an official juridical document attesting the validity of the group in question as a real juridical body, which can be held responsible for its agreements, pays taxes, etc. During the years, a number of ways of organizing have been developed, and today three main types of juridical bodies are operating in the NAS fishery: fishery co-operatives with one or more owners (in some cases up to 15 owners), limited companies typically owned by a person or an enterprise with brigades of fishermen employed seasonally by contract, and private economies, where one or more fishermen register as a small private company in order to obtain only the most basic juridical rights and obligations. To some extent, the forms of organization tend to overlap (a co-operative might e.g. also have an outside non-fisherman owner, who employs brigades by contract), but in general these three groups can be distinguished. The nuclear unit of the whole business is the brigade, which tends to operate as an independent body, with a brigadier, who represents his group of 3-10 fishermen (usually from the same village), and makes agreements with the project (e.g. in most cases with Aral Tenizi), employers and buyers. The role of the brigade has been bigger than initially expected, and the reason for this should be found in the description of the transition phase above. While most fishermen have a desire to become independent and make their own agreements, the situation in nearly all aspects of the trade has been quite uncertain and changeable in recent years. Juridical insight and access to information and credits, good relations to the authorities etc. have been crucial. Therefore, many fishermen have joined together in small unofficial groups, brigades, which then make agreements with co-operatives, limited companies or other, who take these responsibilities.

Today, there are 45 enterprises registered in the NAS fishery. These in average consist in or employ two brigades, and so the sum total of brigades working in the frame of the fishery project is 92. The number of active fishermen varies a little, but a relatively stable figure for the last 1-2 years says that ca. 600 fishermen are active in the brigades. The brigades are divided across the entire distance of the NAS coast line, from Akbasty in the South-West to Karateren in the South-East. An overview of the number of brigades in 2002, gives this picture:

|

Akbasty: 6 |

Akespe: 7 |

Kosaman: 2 |

Tastubek: 6 |

|

Djambul: 17 |

Aralsk: 14 |

Akshatau: 3 |

Kambash: 1 |

|

Akamotkel: 9 |

Bugun: 10 |

Karashalan: 1 |

Kyzylzhar: 3 |

|

Raim: 1 |

Shomishkol: 1 |

Zhanakurilis: 1 |

Karateren: 10 |

The challenge for the future co-operation with fishery brigades lies above all in securing that fishermen gain more real influence on their situation, incl. ownership of the means of production. This process has started, and is moving clearly in the direction of decentralization and local responsibility. It should also not be forgotten however that in a number of cases, the ownership of a few or, most frequently, only one person, has been a necessary way of creating sustainable new business structures at all, and that some co-operatives have come to function well in this manner. Many of these will gradually move towards a higher degree of common ownership and involvement of the fishermen. One instructive case can be mentioned: In the co-operative Kuanysh in the village Karateren, which was founded in 1999, fishermen were initially simply joining together to re-group themselves outside the economical and juridical calamities of the old structures. There was to be equal ownership and common decisions on all questions. These aims are still held high, but the way to get there demanded keen and able activity in a number of fields which simply could not be equally detailed managed by all. Co-founder of the co-operative and currently its leader, Batyrkhan Prikeev, tells: